I am delighted to be exhibiting at this year's 'Photo London' - bringing together the world's leading galleries in a major international photography Fair at Somerset House from 16-19 May. Showcasing new and rarely seen works by Vikram Kushwah, Sebastian Edge and Jamie Gallagher.

Notton Gallery, Booth D15

Public and VIP Access Hours

- Wednesday 15 May: VIP: 11:00 - 21:00

- Thursday 16 May : VIP: 11:00 - 13:00 Public: 13:00 - 20:00

- Friday 17 May: VIP: 11:00 - 13:00 Public: 13:00 - 20:00

- Saturday 18 May: VIP: 11:00 - 12:00 Public: 12:00 - 20:00

- Sunday 19 May : VIP: 11:00 - 12:00 Public: 12:00 - 18:00

-

The Education I Never Had

Vikram KushwahFor 35 years, throughout the course of my entire life, my father has been a schoolteacher at a government school in rural Uttar Pradesh, one of the poorest states in India. Until February of this year, I had never once been to his school. My wife tried on multiple occasions to organise a visit, but he refused each time. Only when I told him that I wanted to do a photo story before he retires next year did he begrudgingly arrange a visit.

My father is the son of a farmer, the youngest of six children who survived infancy. The school in which he works has no electricity and in the hot summer months, classes are held under a large Ficus tree. In the spring, during examination season, I marvel as I watch him write results in large exam ledgers spread across my parents’ coffee table. When he finishes, he rolls the ledgers, which look as if they survived the Victorian Era.

My father was 25 when he was arranged into a marriage with my mother, who was only 16. Less than a year later, I was born. By the time I was three-years-old, my father had sent me to a boarding school in the Himalayan foothills, not because he did not love me, but because he wanted a better life for me than what he had for himself, a better life than the children at the village school where he taught.

For the 1980s, my father was incredibly progressive and forward-thinking. He and my mother had no other children, as they knew they could not afford this type of education for more than one child. Really, they could not afford it for me either. They lived in a one-room shack for eighteen years while I played cricket and studied physics with the sons of diplomats.

This year, on the Indian festival of Holi, I received a phone call from my cousin, who still lives in my father’s ancestral village with his mother and father, as well as his wife and two kids. He was drunk when he called. He asked about my life in the UK, and he lamented about our other cousin who has been missing since we were children. When we hung up the call, I knew I could have been him.

The children in these images are beautiful, playful, diverse—simply, they are human. Yet, their intellect and talents may never fully be expressed as they are also poor. These children represent my family—every member of it having been educated in a school like this… except for me.

There is a cliché about being a photographer—that photographers are both part of and yet, inherently separate from what they are photographing. Photographing in my father’s school, I felt deeply part of the scene. His meagre government teaching salary somehow, against the odds, provided me with an extraordinary life—one in which I became a photographer (a profession my parents still do not understand), married a foreigner (another difficult concept initially for them) and moved abroad (perhaps the hardest of all for them to accept). This government school is the India I came home to during school holidays, while my classmates went on lavish vacations to Dubai and America. Of course, I never told my classmates that my father taught in a government school. To avoid being bullied about my impoverished background, I lied and told them he was a teacher in Delhi Public School, which was far more respectable. Photographing at his school, I knew it was both my India and not at all my India.

Despite being quite a simple man, my father knew there was more to the world—beyond dirt-floor classrooms and decades-old textbooks. He wanted me to find what was out there, even though it meant that I would leave him behind, time and again. Yet, as in most journeys, there is a return, and after seeing so much of the world, really, what I wanted most was to come back to him, to know him and his life, and to understand his sacrifices.

-

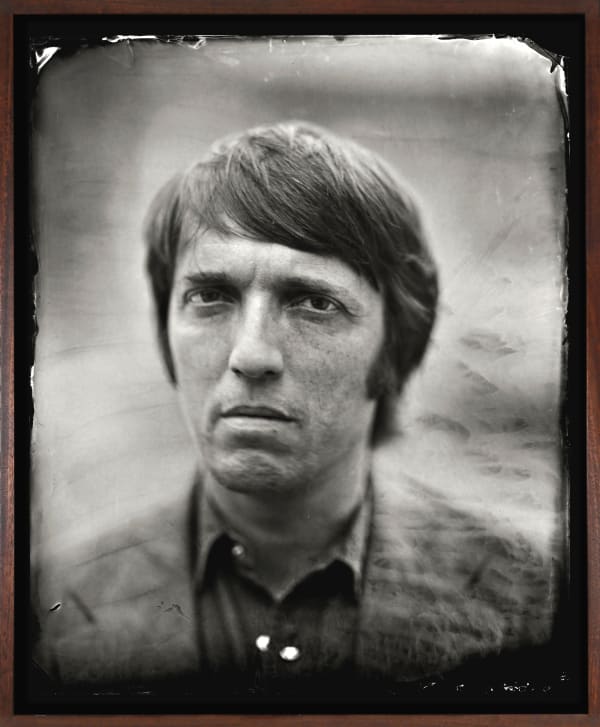

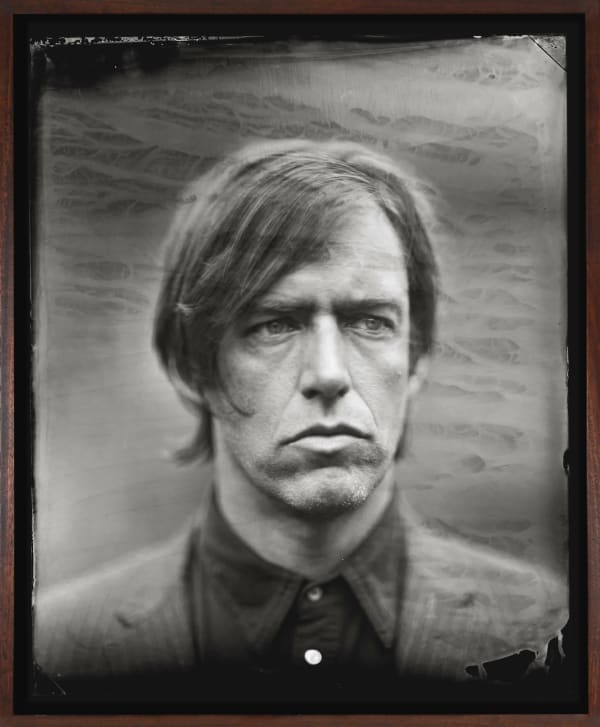

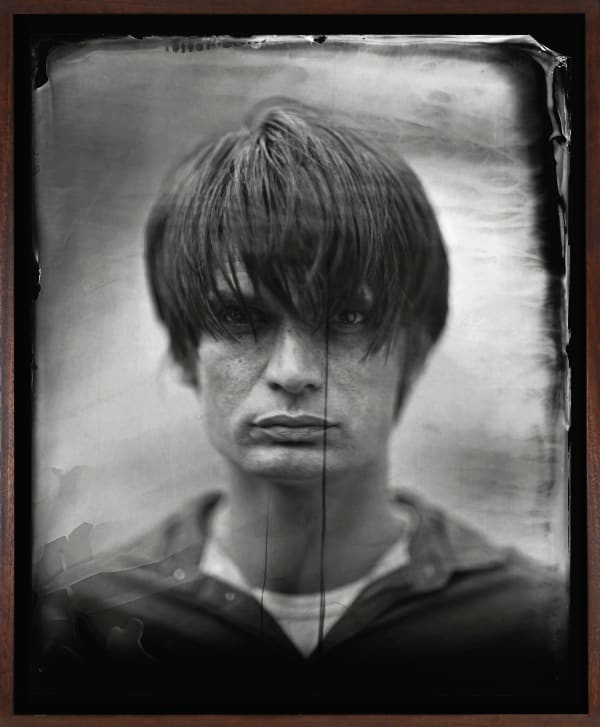

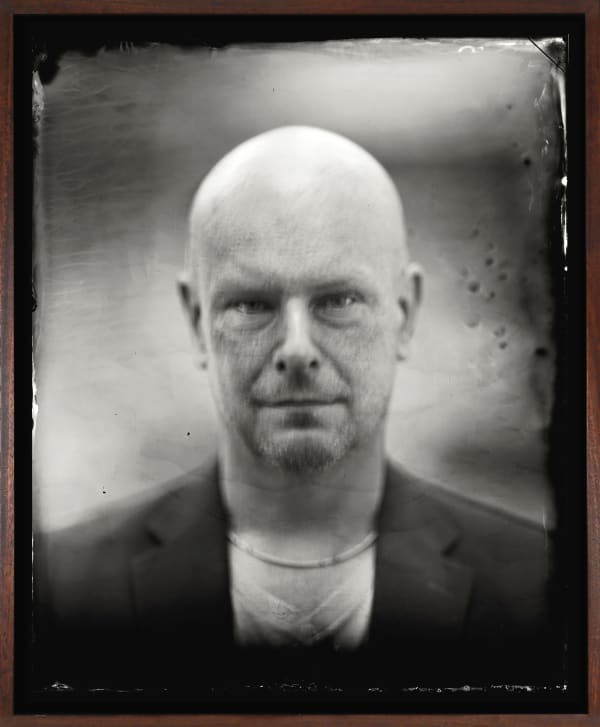

RADIOHEAD: The Collodion Wet-Plate Portraits

Sebastian Edge -

RADIOHEAD

Wet-Plate Collodion